- Home

- S. W. J. O'Malley

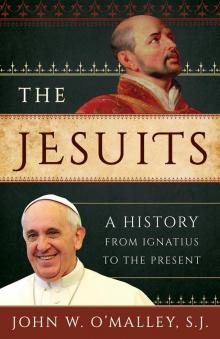

The Jesuits

The Jesuits Read online

Praise for The Jesuits

“Only John W. O’Malley is today in a position to offer a sweeping scholarly yet accessible overview of the extraordinarily rich and complex history of the Society of Jesus—from Ignatius of Loyola to Pope Francis.”

—Robert A. Maryks, Boston College, editor in chief of the Journal of Jesuits Studies

“John O’Malley’s brief history of the Jesuits is both readable and accurate. From the order’s official foundation by the Basque nobleman Ignatius of Loyola in 1540 to the recent election of a Jesuit pope, the story of the Jesuit order as told here is one of extraordinary consistency, flexibility, and persistence. O’Malley provides a dispassionate account of the role of Jesuit education throughout the world, and of the often violent political reactions to the order’s perceived power. Readers will be inspired to follow up on the more detailed sources listed here, but John O’Malley’s text stands alone as an authoritative and illuminating guide.”

—Elizabeth Cropper, dean, Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, National Gallery of Art

THE JESUITS

A History from Ignatius to the Present

JOHN W. O’MALLEY, SJ

A Sheed & Ward Book

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com

16 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BT, United Kingdom

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright © 2014 by Editions Lessius, Brussels. All rights reserved. First published as Histoire des jésuites d’Ignace de Loyola à nos jours

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

O’Malley, John W.

The Jesuits : a history from Ignatius to the present / John W. O’Malley, SJ.

pages cm

“A Sheed & Ward Book.”

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-3475-8 (cloth : alk. paper)—ISBN 978-1-4422-3476-5 (electronic) 1. Jesuits—History. I. Title.

BX3706.3.O425 2014

271’.53—dc23

2014007970

™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992.

CONTENTS

Important Dates in the History of the Society of Jesus

Preface

1 Foundations

2 The First Hundred Years

3 Consolidation, Controversy, Calamity

4 The Modern and Postmodern Era

Epilogue: Looking Back and Looking Ahead

Further Reading

Notes

About the Author

IMPORTANT DATES IN THE HISTORY OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS

1491 Birth of Ignatius of Loyola

1521 Battle of Pamplona, where Ignatius was wounded and his conversion begun

1534 Ignatius and six fellow students at the University of Paris pronounce a vow to go to Jerusalem

1540 Official approval of the Society of Jesus by Pope Paul III

1542 Francis Xavier arrives in India

1547 Portuguese Jesuits arrive in Brazil

1548 Jesuits open their school in Messina, Italy

1556 Ignatius dies in Rome

1558 The First General Congregation approves the Constitutions and elects Diego Laínez to succeed Ignatius

1583 Matteo Ricci and Michele Ruggieri enter China

1614 Jesuits and other missionaries expelled from Japan Publication of the Monita Secreta

1622 Canonization of Ignatius and Xavier

1656 Pascal publishes the first of his Provincial Letters

1704 Condemnation of “Chinese Rites” by Pope Clement XI

1754 Outbreak of the “War of the Seven Reductions”

1759 Expulsion of the Jesuits from Portugal and Portuguese dominions

1764 King Louis XV issues the royal decree suppressing the Jesuits in France

1767 Jesuits suppressed in Spain and Spanish dominions and their properties seized

1773 Worldwide suppression by Pope Clement XIV, Dominus ac Redemptor

1801 Pope Pius VII validates the existence of the Society in Russia, Catholicae fidei

1814 Worldwide restoration of the Society by Pius VII, Sollicitudo omnium ecclesiarum

1965 Election of Pedro Arrupe as superior general, Thirty-First General Congregation

2013 Election of Jorge Mario Bergoglio as Pope Francis, the first Jesuit pope

PREFACE

Within a few decades the Society of Jesus will observe the five hundredth anniversary of its founding in 1540. During the course of almost five centuries, it has had a rich, complex, and often tumultuous history. Much admired and much reviled, it has from the beginning eluded facile categorization. On the most basic level, the Society is simply a Roman Catholic religious order, whose members pronounce the traditional vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Like the members of other orders, the Jesuits engage in the traditional ministries of preaching and administering the sacraments. Like the members of many orders, Jesuits travel as missionaries to distant lands and peoples. “The world is our house,” as Jerónimo Nadal, an early and extremely influential Jesuit, put it.1

About a decade after their founding, however, the Jesuits began to operate schools for lay students, something no religious order had ever done before in a systemic way. At that point they began to assume a profile that was altogether distinctive. Through the schools they were drawn into aspects of secular culture in ways and to a degree unprecedented for a religious order. Jesuits became poets, astronomers, architects, anthropologists, theatrical entrepreneurs, and much more.

They were much appreciated. They were also feared and hated, even by many Catholics. Histories written about them have for centuries reflected this bifurcation: the Jesuits were saints; the Jesuits were devils. Of course, there were always more judicious appraisals, but only about twenty years ago did an almost seismic shift occur as historians began approaching the Jesuits in a more even-handed way, asking the simple and neutral question, “What were they like?”

This approach has been extremely fruitful and has generated an unprecedented outpouring of studies on every aspect of the Jesuit enterprise. The quality of this new research is consistently high. We now know more about the Jesuits than ever before, and we see them in new and helpful perspectives.

The pages that follow are informed by that scholarship. In them I limit myself to two objectives: (1) to provide in almost skeletal form the basic narrative of the origin, development, triumphs, and tribulations of the Society of Jesus up to the present; (2) to provide through almost arbitrary choice descriptions in detail of a few undertakings—lest the narrative soar too high and lose touch with the concrete reality that is history. This small book will have been a success if it whets readers’ appetites to read further into the fascinating history of the Jesuits.

1

FOUNDATIONS

On February 2, 1528, a devout Basque nobleman, Iñigo de Loyola, arrived in Paris. At the advanced age of thirty-seven, he intended to pursue a degree at the university. Iñigo enrolled in the Collège de Montaigu, where he remained for a year b

efore transferring to the Collège Sainte-Barbe. At Sainte-Barbe he shared lodgings with two much younger students, Pierre Favre and Francisco Xavier. Friendships formed among them and then expanded to include four more students—Diego Laínez, Alfonso Salmerón, Nicolás Bobadilla, and Simão Rodrigues. At this time Iñigo began to refer to himself as Ignacio or Ignatius, the name by which he has been known ever since.

Inspired by Ignatius, these “friends in the Lord,” as they described themselves, vowed in the summer of 1534 to travel together to the Holy Land to live at least for a while where Jesus lived and to work for “the good of souls.” However, if because of the disturbed political situation in the Mediterranean they could not get passage, they would offer themselves to the pope for whatever ministries he thought best. On August 15 during a mass celebrated by Favre, the only priest among them at the time, they bound themselves to this course of action as well as to a life of poverty. Since they all in fact intended to be ordained, they were already committed to a life of celibate chastity. They did not realize at the time that on that fateful August 15, 1534, they took the first step that led six years later to the founding of the Society of Jesus.

Before these seven left Paris to begin their journey, they were joined by three more students—Claude Jay, Paschase Broёt, and Jean Codure. By 1537 the ten, now holding their prestigious Master of Arts degrees from the University of Paris, had arrived in Venice. There they were ordained and awaited passage eastward. As they waited they engaged in preaching and other ministries in northern and central Italy. When asked who they were, they now responded that they were members of “a brotherhood of Jesus,” in Italian una compagnia di Gesù (in Latin, Societas Iesu). As the months passed and turned into years, they realized that political tensions made the trip to the Holy Land impossible. What were they to do? Should they stay together, and even take more members into their compagnia? If so, should they go so far as to try to found a new religious order?

In the spring of 1539 they gathered in Rome. Over the course of three months they met almost daily to deliberate about their future. Not only did they quickly decide to stay together and found a new order, but as the weeks unfolded they were able to sketch the contours of the order in sufficient detail to submit their plan to the Holy See for approval. They called the document their Formula vivendi, their “plan of life.” The Holy See, after raising questions, hesitating, and then making small modifications, accepted the Formula and incorporated it into the bull of approval signed by Pope Paul III, Regimini militantis ecclesiae. With the bull’s publication on September 27, 1540, the Society of Jesus officially came into existence.

On April 19 the next year, the members elected Ignatius their first superior general, an office he held until his death in 1556. Even before the election was settled, Francisco Xavier was, at the behest of King John III of Portugal, already on his way to Lisbon to prepare for his departure as a missionary in India. He arrived at his overseas destination two years later to become the most famous missionary in modern times. While Xavier traveled beyond India to evangelize other parts of southeast Asia, Ignatius, by contrast, sat at his desk in Rome guiding the new Society, a task that included writing Constitutions, in which structures and procedures were spelled out in much greater detail than in the Formula.

From ten members in 1540, the Society grew at almost breathtaking speed to a thousand by the time Ignatius died sixteen years later. Except for the British Isles and Scandinavia, it had established itself in virtually every country of western Europe, in most of which it opened schools, already the Jesuits’ trademark ministry. It had also established itself overseas. Of the thousand members in 1556, some fifty-five were in Goa in India and twenty-five in Brazil, where they had arrived in 1547. Two years later Xavier entered Japan, where he laid the groundwork for the Jesuits’ most successful mission in the Far East. He died in 1552 on the verge of entering mainland China.

The Society of Jesus was only one of several new religious orders founded at about the same time, but it grew and achieved a status that far exceeded the others. The Theatines, founded in 1524, had by mid-century only thirty members, all of them in Italy. The Barnabites and Somascans had comparably small numbers, who also were all in Italy. How to explain this discrepancy?

THE SOCIETY OF JESUS TAKES SHAPE

When the ten founders drew up the Formula, they seemed to envisage the Society as an updated version of the so-called mendicant orders such as the Dominicans and Franciscans founded in the thirteenth century. They described themselves as engaging primarily in the same ministries of preaching and hearing confessions. They, like the Dominicans and Franciscans, saw these ministries as almost by definition itinerant and without geographical limits, which thus implicitly entailed overseas missions. They in fact conceived the Society as essentially a missionary order. In the Formula the founders made explicit their dedication to “missions anywhere in the world” by a special vow that obliged them to be ready to travel “among the Turks, or to the New World, or to the Lutherans, or to any others whether infidels or faithful.” (Because this vow was in addition to the customary three of poverty, chastity, and obedience, it is commonly referred to as the Fourth Vow.) Although they specified the pope as the one who would send them on these missions, they soon realized this provision was impracticable, and in their Constitutions they invested the superior general with the primary responsibility in this regard. Nonetheless, the Jesuits and others came to interpret the vow as giving the Society a special relationship to the papacy. It was not, however, as it is often erroneously described, a vow of “loyalty to the pope.” It was a vow to be missionaries.

Although the founders were all priests, within a few years the Jesuits, like the mendicants, made provision for nonordained members. At times in the history of the Society these “lay brothers” (or, better, temporal coadjutors, which is the Jesuits’ official term for them) constituted about a third of the membership. They served the Society as cooks, buyers, and treasurers and in other practical tasks. Some were highly skilled professionals—architects, for instance, and artisans of various types. Among the more famous was the painter Andrea Pozzo (1642–1709), but there were others of extraordinary talent.

Even within the parameters of the Formula, the Jesuits made adjustments that set them off from their mendicant model, some of which shocked contemporaries and made the Jesuits suspect in their eyes. The Jesuits would not wear a distinctive religious habit, for instance, and they retained their family names. Instead of a set term of, say, three or six years, they elected their superior general for life and accorded him much more authority than did the mendicants. The name they insisted upon for themselves, the Society of Jesus, struck others as arrogant and self-serving.

Most controversial, however, was the provision in the Formula that the members not recite or chant the Liturgical Hours such as matins and vespers in choir, which up to that point was considered almost the definition of a religious order. By forgoing that traditional practice, which required members of the community to assemble for prayer several times a day, the founders argued that they had greater flexibility to meet the needs of ministry at whatever hour of day or night they occurred.

Such provisions, important though they were in the eyes of contemporaries, do not adequately explain why the Jesuits grew so rapidly and achieved such a distinctive culture. Other factors were more important, such as the international and cosmopolitan background of the original ten members and the prestige of their Paris degrees. Determinative, however, was the person of Ignatius, who influenced the Society in a number of ways, but perhaps nowhere more profoundly than as author of the Spiritual Exercises.

Born probably in 1491, Iñigo/Ignatius followed the usual course for a younger son in a family of his social class. When he was probably about seven, he left the family castle at Loyola to serve first as page and then as courtier in the household at Arévalo of Juan Velásquez de Cuéllar, chief treasurer of Castile. He remained there about ten years. At Arév

alo he learned to dance, sing, duel, read and write Spanish, and get into brawls.

When Velásquez died in 1517, Ignatius entered the service of Don Antonio Manrique de Lara, duke of Nájera and viceroy of Navarre. When French forces invaded Navarre in 1521 and advanced on Pamplona, Ignatius was there to defend it. During the crucial battle, a cannonball shattered his right leg and damaged the left. The wound was serious, and despite several excruciatingly painful operations, it left him with a limp for the rest of his life.

He recuperated at his early home, the castle of Loyola. His religious conversion took place during those long months. He found at the castle none of the tales of chivalrous knights and their ladies that he loved to read and that might now relieve his boredom. In some desperation he turned to the only literature at hand—the Life of Christ by Ludolf of Saxony and excerpts from The Golden Legend, a medieval collection of lives of the saints. The latter led him to speculate about the possibility of fashioning his own life after the saints and of imitating their deeds.

In his imagination, however, he debated for a long time the alternatives of continuing according to his former path as courtier and soldier, even with his limp, or of turning completely from it to the patterns exemplified especially by Saint Dominic and Saint Francis of Assisi. He found that when he entertained the first alternative he was afterward left dry and agitated in spirit, whereas the second brought him serenity and comfort. By consulting his inner experience in this way, he gradually came to the conviction that God was speaking to him through it, and he finally resolved to begin an entirely new life. This process of self-examination by which he arrived at his decision became a distinctive feature of the way he would continue to govern himself and became a paradigm of what he would teach others.

Once his physical strength was sufficiently restored, he set out from Loyola on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. On the way he planned to spend a few days at the small town of Manresa outside Barcelona to reflect upon his experience up to that point. For various reasons, including originally the outbreak of the plague, he prolonged his stay there for almost a year. He gave himself up to a severe regimen—long hours of prayer, fasting, self-flagellation, and other austerities that were extreme even for the sixteenth century. However, this program sent him into such a deep spiritual and psychological crisis that at one point he was tempted to suicide.

The Jesuits

The Jesuits